The School of Love, 2015-2016, Enamel on canvas, © Courtesy : The Artist and Wilkinson Gallery, London

Allusions to paintings by great masters, and to seedy going on in the woods, combine for a fascinating new exhibition by George Shaw.

There’s also a set of fairly surprising new works that hit you when you walk in to My Back to Nature in the Sunley Room at the National Gallery.

Fourteen charcoal drawings entitled The Sadness of the Middle-Aged Life Model bring us a naked George in all his glory posing in the position of the stations of the cross, which he would have seen in the Catholic church of his upbringing. All the religious paintings in the National Gallery, where he has been Rootstein Hopkins Associate Artist for the past two and a half years, have clearly made quite an impression, though I remember a number of (less revealing) self portraits from his youth in his exhibition at The Herbert.

They create a good, surprising, introduction to the exhibition.

The Sadness of the Middle-Aged Life Model (10), 2015, Charcoal on paper, © Courtesy : The Artist and Wilkinson Gallery, London

George said he found the National Gallery rooms nearly all contained scenes from woodland, women parading around and many had Jesus. So with the self-portraits, all three elements of that can be seen in this exhibition.

The paintings are a mixture of sizes, all in the usual Humbrol paint but with a move on to canvas rather than board. Thee Afternoons (Study for Drunken Silliness), The Tossed and The Lost are small works focusing on finds in the woods – abandoned colour pornographic photos, empty bottles, leaves concealing things.

A Revel Before Half-Term features a large canvas with the trees standing darkly round, cans scattered about. The Heart of the Wood shows a small circle of bricks as well as the signs of recent partying; is it the base of a fire, or some more sinister black magic practices? The trees aren’t talking.

Studies for Hanging Around are three single trees, a reference to the crosses of the Crucifixion, and another clear influence from the residency, where he said he had become obsessed with the wood on the cross. The Foot of the Tree is a wooden stump left behind and Verso and Recto are reminiscent of some of his earlier works, with muddy paths leading away. The Uncovered Cover shows a blue cloth partly covered with leaves and concealing – anything or nothing?

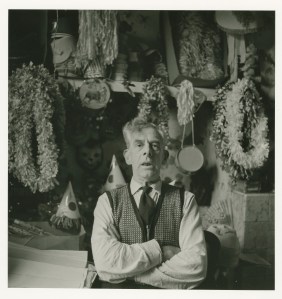

The Old Master, 2015-2016, Enamel on canvas, © Courtesy : The Artist and Wilkinson Gallery, London

Another section of the gallery, George said at the press preview, he saw as the Adam and Eve corner.

The Old Master and The Old Country represent the male and female – or as George put it “someone’s gone into the woods and painted a cock on a tree – then there’s a very suggestive tree”. Ok ….

The graffiti is crudely and unnecessarily-added amongst the wooded scene, a reminder that it’s not in the depths of the woods but just yards from a Coventry housing estate. The tree has a deep, gaping crevice painted with care and attention.

The School of Love is a painting of an abandoned mattress, dumped and unloved now, deep in the greenery.

Another work is an unusual self-portrait – George seen from behind up close to a tree: “I’m looking at the Observer Book of Moss,” he joked. “It’s called Call of Nature – what else?”

You’ve Changed is a set of nine small paintings of trees, all different, all with holes in their trunks somewhere, or cracked open; George referred to Youtube references to men who liked sexual liaisons with trees, finding the sexual in the suburbs.

George’s three paintings in the style of Titians Diana and Actaeon works command one wall.

A tarpaulin he found in the wood, hanging like a soft, sensuous material over one tree, represents the pulled-aside curtain, and the work is called The Rude Screen, a play on the rood screen which pre-reformation separated the church congregation from the priest.

The Rude Screen, 2015-2016, Enamel on canvas, © Courtesy : The Artist and Wilkinson Gallery, London

A hollybush stuffed full of pornographic pictures that he saw as a child – “I have no idea who put it there, it was almost like a branch of John Menzies” – was the inspiration for the painting representing the bathing beauties and is called Möcht’ ich zurücke wieder wanken . Hints of naked flesh and raised clothes can be seen on the images.

The third painting, representing the killing, is entitled Every Brush Stroke is Torn Out of My Body, and shows red paint randomly daubed on a tree, with another tree displaying a target. Again, it’s the imposition of the urban, peopled world into what is supposedly natural.

There is also a film of George at work at the gallery, talking about his influences, and visiting a wood (though unfortunately not the Tile Hill one), which is definitely worth seeing.

It’s a long time since we’ve seen a new body of work from Shaw but it’s been well worth the wait, and also made me eager to go back to some of his inspirations in the rest of the Gallery.